Abhishek Mukherjee

Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor at CricketCountry. He blogs at ovshake dot blogspot dot com and can be followed on Twitter @ovshake42.

Written by Abhishek Mukherjee

Published: Apr 14, 2015, 07:36 AM (IST)

Edited: Nov 24, 2016, 03:00 PM (IST)

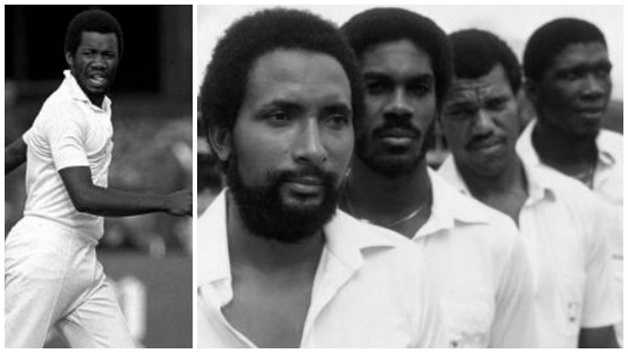

The pack of West Indian fast bowlers steamrolled over oppositions one after another from mid-1970s to mid-1990s.However, the scariest quintet — Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner, Colin Croft, Malcolm Marshall — took field together only once, on November 24, 1981. Abhishek Mukherjee looks at the day when the strongest bowling attack in ODI history could not prevent a West Indies defeat.

Andy Roberts was the first to arrive. Michael Holding joined a couple of years later. Wayne Daniel made his debut in the interim, and after another couple of years Joel Garner and Colin Croft. The Kerry Packer era saw Sylvester Clarke and Malcolm Marshall arrive on the scene. As the big guns returned, Marshall stayed on.

Clive Lloyd continued with his four-fast-bowler strategy. Marshall was rising up the ladder, but the ascent to the top spot in world cricket would take some time. Meanwhile, the world had to contend with the wily aggression of Roberts, the brutal pace of Holding, the relentless accuracy of Garner, and the mean hostility of Croft.

The strategy of the opposition batsmen was a no-brainer, especially in ODIs. They had to see off the quartet, scoring as many runs as possible off the fifth bowler — usually Viv Richards or Larry Gomes.

Holding missed West Indies’ first match of Benson & Hedges World Series Cup 1981-82 at MCG, but it did not matter: Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes put up 182 for the opening stand, Roberts and Marshall shared five wickets between them, and the Caribbeans prevailed.

Australia suffered another loss, this time against Pakistan at MCG. West Indies replaced Gomes with Holding, thus going in with Roberts, Holding, Garner, Croft, and Marshall for the only time in history in an international match.

Super Cat shines

The SCG crowd had to wait for pace show. West Indies batted first, and Greenidge and Haynes got off to a stand that was more solid than spectacular. They added 64 in 76 minutes, but Jeff Thomson was formidable even in the dying stage of his career. In a four-over spell he held Haynes off his own bowling, clean bowled Greenidge, and had Faoud Bacchus caught at point.

Lloyd joined Richards at 98 for 3, and hell broke loose after a few cautious overs. The pair added 72 in less than an hour before Richards was run out. Lloyd continued, his heavy bat smashing the ball with extraordinary force and sending the ball to the fence with pinpoint accuracy. Shaun Graf had an economy rate of 3.70 going into the match; he conceded 56 from 9 overs and never played again.

Lloyd eventually fell for a 59-ball 63, and Deryck Murray followed soon. An entertaining 32-run stand between Marshall and Roberts made sure West Indies reached 236 for 8 from 49 overs. Thomson finished with 3 wickets, but Geoff Lawson’s 10-2-28-2 also deserves a mention. The Australians, having bowled an over less, had to cough up.

Famous Five

What instructions would Greg Chappell given to Bruce Laird and Rick Darling as they walked out? “See them off and score off the fifth” was not an option, which meant that the batsmen had only their bravado and the occasional loose ball to bank on.

It did not take long: Holding bowled a vicious bouncer, Darling tried to hook, the ball took the edge, and Murray pouched the catch; Chappell was trapped leg-before by Roberts the next over; the score read 8 for 2.

The situation was tailor-made for Allan Border. It was not the first time that he was up against such adverse situations, and it would certainly not be the last. The West Indians were relentless: Holding and Roberts gave way to Marshall and Garner, with Croft holding up the rear, but Border and Laird were unflappable.

It eventually took a “brilliant piece of fielding” from Haynes to run Border out. The partnership had been worth 82 in 72 minutes. They still needed 146 when Kim Hughes walked out. Of specialist batsmen, Graeme Wood — as gritty as any cricketer ever born — was the only man left in the pavilion.

Hughes’ career would not last long, but this was his day, as it was Laird’s. Had he failed, critics may have been after Chappell, for the situation perhaps demanded for the dour Wood more than the flamboyant Hughes. However, Hughes was in good form that summer, having scored 106 and 67 in his previous two innings.

As Laird and Hughes eased into the proceedings, the West Indian shoulders started to drop. The morale took a further blow when Greenidge dived to save a “hot drive” from Hughes and had to leave with a “jarred leg”.

By the time Laird, 12th man in the match against Pakistan, brought up his hundred, Australia were in a commanding position. The crowd invaded the ground, and when they eventually left, a stump was found missing at the Hill End. Play was held up as a replacement was summoned.

What followed?

– Croft never played another ODI.

– West Indies stormed into the best-of-five finals with 7 wins in 10 matches. Australia were tied with Pakistan on four wins each, but the hosts went through on run rate, though this took a murky turn a report on The Age that accused West Indies of throwing the match. This eventually led to the infamous Lloyd vs David Syme & Co. Ltd lawsuit.

– West Indies won the first two finals by big margins before Australia pulled one back in the third. West Indies sealed the tournament with a victory off the fourth.

Brief scores:

West Indies 236 for 8 in 49 overs (Viv Richards 47, Clive Lloyd 63; Jeff Thomson 3 for 55) lost to Australia 237 for 3 in 47 overs (Bruce Laird 117*, Kim Hughes 62*) by 7 wickets with 12 balls to spare.

Man of the Match: Bruce Laird.

(Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor and Cricket Historian at CricketCountry. He blogs here and can be followed on Twitter here)

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.