Abhishek Mukherjee

Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor at CricketCountry. He blogs at ovshake dot blogspot dot com and can be followed on Twitter @ovshake42.

Written by Abhishek Mukherjee

Published: Jun 07, 2016, 07:13 AM (IST)

Edited: Jun 07, 2016, 01:20 PM (IST)

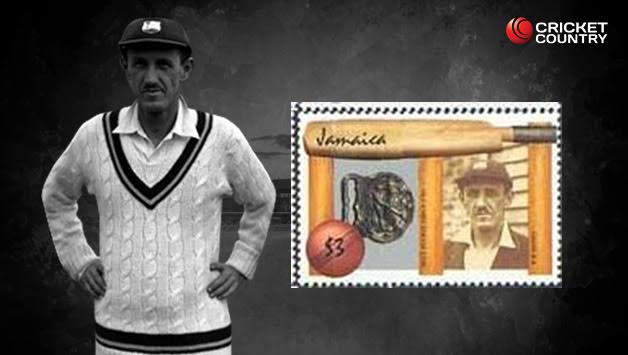

Born June 7, 1894, Robert Karl Nunes was West Indies’s first Test captain and wicketkeeper. A gritty, technically correct left-handed batsman and an occasional gloveman, Nunes led West Indies in their first three Tests on their maiden tour of England. Abhishek Mukherjee looks back at the one of the early Calypso champions.

Even if he had done nothing else, Robert Karl Nunes would have been remembered by West Indies cricket as their first Test captain and wicketkeeper. But there was more to Nunes than that. A left-handed batsman with a polished technique, Nunes could bat anywhere in the line-up. With the big gloves he was at best competent, but was forced to take up roles that were possibly beyond him.

As captain Nunes was strict and hard-nosed. His wiry frame and toothbrush moustache did not command respect at first, but his wards soon found out that Nunes was more Hitler than Chaplin when it came to being a disciplinarian.

From 61 First-Class matches, for Jamaica and various representative West Indian teams, Nunes scored 2,695 runs at 31 with 6 hundreds to go with 39 dismissals. These included 4 Tests, which fetched him 245 runs at 31 with 2 fifties, along with 2 catches.

The numbers do not seem spectacular, but it must be remembered that Nunes played in an era when wicketkeepers were not expected to do well with bat (though he did not always keep wickets). He was also not among the great travellers: while his 1,253 overseas runs came at 22, his 1,442 runs at home came at 50.

His low dismissal count can be attributed to the fact that he often played for weak teams, and as a result fielded in only one innings per match. Indeed, West Indies lost all 3 Tests by an innings Nunes kept wickets in.

Dulwich and War

Born in Kingston, Nunes went to Wolmer’s Boys School, often referred to as University of Cricket in the city for its rich history. One of the oddities of Wolmer’s is the fact that they have provided six Test wicketkeepers (Nunes, Ivan Barrow, Gerry Alexander, Jackie Hendriks, Jeff Dujon, and Carlton Baugh), which must be a world record. Wolmer’s also gave the world Allan Rae, Patrick Patterson, and Gareth Breese.

Nunes went to Dulwich College, where he played alongside the Gilligan brothers, Harold and Arthur. He topped the college averages in 1911 and 1912. In 1911 he added 344 with CV Arnold, still a record for Dulwich College. He was emerging as a talent when World War I broke out.

He joined the British Army, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in British West Indies Regiment in February 1917. He later became Captain, albeit on a temporary basis. He returned to England in July 1918. Three months later he joined RAF as captain.

He was posted with Squadron No. 236 at RNAS Station Mullion near Cornwall, where he was a part of patrols on the lookout for German submarines. He served military duty till June 1919.

The 1923 tour

Once cricket resumed after The Great War, Nunes tried his hand at The Oval, for both Surrey Club and Ground, and Surrey Second XI. Then he went back to Jamaica and played for Kingston CC.

When a combined West Indian side toured England in 1923, Nunes was named deputy to Harold Austin. He was also not the main wicketkeeper (George ‘Fatty’ Dewhurst assumed the duty behind stumps).

On his First-Class debut, against Cambridge, Nunes was asked to open batting. Cambridge led by 91, and Nunes stood firm in the second innings, registering 59, his maiden First-Class fifty. The tourists were reduced to 79 for 7 before Nunes pushed them beyond the 91-run mark.

That aside, Nunes scored two other fifties (89 against Oxford and 61 against Essex) in consecutive innings. Nunes’ 455 First-Class runs came at 20.

However, the tourists did a splendid job, winning 6 matches and losing 7 out of 20. If one included Second-Class matches, the tally read 13 wins, 8 draws, and 7 defeats.

A lot of hundreds

Nunes did not score big in the inter-island matches, but was back in business once MCC came over in 1925-26. He walked out after Jamaica trailed by 221 runs, and though there was some resistance from Tommy Scott, the hosts were soon reduced to 144 for 4.

But Herbert Campbell hung on, helping Nunes add 58. Edgar Rae (father of Allan) hung around as well, and the match was saved. Nunes remained unbeaten on 140 — the first hundred by any West Indian against a touring MCC side. He rounded off the series with 83 against them.

The Jamaica Cricket Board was founded that same year, with Nunes playing a crucial role in its formation.

Lord Tennyson’s team came over next season. This time Nunes scored a career-best of 200 not out — the first double-hundred by a West Indies batsman against any visiting side. He scored 108 in the innings that followed, making it 541 runs in 4 innings at 270.50.

The 1928 tour

The selectors did not look beyond Nunes (a white man, of course) as captain for the historic 1928 tour of England. The composition of the side is indicative of the extent of inter-island politics in West Indian cricket of the era: of the 17 men, 5 were from Barbados, and 4 from each of Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana.

The composition meant that the side turned out to be somewhat uneven. For example, there was no second wicketkeeper, which meant Nunes (himself not a frontline wicketkeeper) had to assume duties behind the stumps throughout the tour. He still finished 5th on batting charts with 798 runs at 23. If one included Second-Class matches as well, Nunes scored 1,001 runs at 25.

Nunes scored 76 not out against Oxford, and 102 not out against Civil Service, his first hundred of the tour. Against Glamorgan he scored 127 not out, his only First-Class hundred outside West Indies.

As for the Tests, every single one turned out to be a disaster. England won all three Tests by an innings. The West Indians were no match for the supreme batsmanship of Jack Hobbs, Herbert Sutcliffe, and Ernest Tyldesley; neither could they cope against the bowling of Tich Freeman, Maurice Tate, and Vallance Jupp.

Nunes put up a dogged show in the first innings of the first Test at Lord’s. England put on 401, and at 86 without loss, it seemed George Challenor and Freddie Martin would make a fight out of it.

But Harold Larwood struck, and Tate and Jupp reduced West Indies to 96 for 5. Nunes led a fightback of sorts with a gutsy 90-minute 37, but nobody else (barring the openers) reached 20. West Indies were bowled out for 177. By evening they were 44 for 6, Nunes having fallen for 10.

There was some fight from Joe Small and Snuffy Browne the next morning, but West Indies were still bowled out for 166. The next two Tests followed the same pattern. Nunes reached double-figures 5 times out of 6, but never made it past 20 after the first innings. He finished the series with 87 runs at 14.50.

To make things worse, it was a terrible tour for West Indies in general. They won 7 matches and lost 12. George Challenor, star of the 1923 tour, failed miserably. They lost to Minor Counties after making them follow-on. Yorkshire bowled them out for 58. Sussex beat them by an innings despite leaving out Tate, KS Duleepsinhji, and James Langridge.

The West Indians even lost to Wales, for whom a 55-year old Syd Barnes turned up out of nowhere and claimed 12 for 116.

The fact that West Indies toured without a specialist wicketkeeper did not help their cause. Wisden was harsh in criticism: “Nunes, as a wicket keeper, having only moderate skill, the absence of Dewhurst — a member of the team of 1923 — was very severely felt.” The Cricketer did not spare Nunes either, mentioning that “he did a horrid job.”

Wisden did not spare the team in general, either (though they made exception to Learie Constantine, who announced himself on the tour): “Unhappily expectations were rudely shattered. So far from improving upon the form of their predecessors, the team of 1928 fell so much below it that everybody was compelled to realise that the playing of Test Matches between England and West Indies was a mistake.”

The one final hurrah

When Sir Julian Cahn brought his team over that winter, Nunes celebrated it with 112. MCC came the following season. There were 4 Tests, one for each major island, but that was not all: there were four captains, every time from the host island.

Thus, Teddy Hoad led West Indies at Barbados, where the Test ended with England on 167 for 3 chasing 287. England won the Trinidad Test by 167 runs, where West Indies were led by Nelson Betancourt.

Maurice Fernandes took over at British Guiana, leading the hosts to a 289-run win — the first in their history. The heroes were Clifford Roach (209), a young George Headley (114 and 112), George Francis (4 for 40 and 2 for 69), and Constantine (4 for 35 and 5 for 87).

After the Test Fernandes probably expected to be retained for the decider at Sabina Park; unfortunately, that was not to happen. He was dropped altogether from the side, as were both Constantine and Francis.

Nunes was recalled as captain. Headley was not a certainty either, but he was from Jamaica. Scott and Freddie Martin, two other Jamaicans, were also in the side. Four Jamaicans — Oscar Da Costa, George Gladstone, Charles Passailaigue, and wicketkeeper Ivan Barrow — made their Test debuts.

That left the selectors three slots, which were distributed among the other three islands: the fortunate trio were Herman Griffith of Barbados, Frank de Caires of British Guiana, and Roach of Trinidad. Roach and Headley became the only ones to play all 4 Tests.

[read-also]381481,124127[/read-also]

Barrow’s inclusion meant that Nunes could afford to give up wicketkeeping duties and concentrate only on opening batting and leading the side. It did not matter: Andy Sandham scored 325 (the first ever triple-hundred), and since it was a timeless Test, England batted till Day Three. They amassed 849.

West Indies were bowled out for 286 despite Nunes gave them “a fair chance”. Batting at the top he top-scored with 66 in 146 balls, but nobody else reached fifty. Freddie Calthorpe refused to declare till the target rose to 836.

West Indies resumed on Day Six, and lost Roach early. However, Nunes and Headley, the locals, batted till stumps, finishing the day on 234 for 1. Nunes was eventually bowled by Ewart Astill the morning after for a 355-ball 92; the pair added 227 in 255 minutes.

Nunes became the first West Indian captain to score two fifties in a Test. Though Jack Grant would emulate him in a few months, they would remain the only ones to do the same till Frank Worrell in 1960-61.

West Indies finished the day on 408 for 5. Headley scored a defiant 223, still the highest fourth-innings score. The match was called off after two days of rain — because the English had to catch the boat back home.

Nunes never played another Test, but played twice in 1931-32 against Lord Tennyson’s XI. He reserved his best for his last First-Class match: having acquired a 174-run lead, the tourists were bowled out for 188. Jamaica needed 363 to win.

Headley opened batting, and Nunes came at No. 3, with the team score on 44 for 1. The stand yielded 242 before Nunes fell for 125. The next two men got ducks, but Da Costa held fort, and Headley, with 155 not out, took Jamaica home.

Post-retirement

Nunes assumed administrative roles after hanging up his boots. An active member of the Jamaican Board, Nunes was elected President of West Indies Board of Control — a post he held from 1945 to 1952.

He was also the West Indian representative at Imperial Cricket Conference from 1947 to 1951, and was instrumental in the beginning of a cricket relationship between India and West Indies, and the emergence of Pakistan as a Test-playing nation.

Nunes served as Chairman of Agricultural Societies Loan Board, and was awarded a CBE in 1951 for “public services in Jamaica”.

Robert Karl Nunes passed away at St Mary’s Hospital, London, on July 23, 1958. He was 64.

On June 6, 1988 a £3 stamp was issued by Jamaica Postmaster General, featuring Nunes and the Barbados Buckle.

(Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor at CricketCountry and CricLife. He blogs here and can be followed on Twitter here.)

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.