Michael Jones

(Michael Jones’s writing focuses on cricket history and statistics, with occasional forays into the contemporary game)

Written by Michael Jones

Published: Jan 02, 2016, 08:19 AM (IST)

Edited: Jan 02, 2016, 06:02 PM (IST)

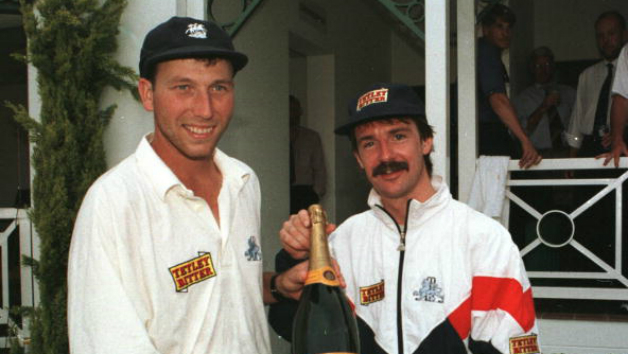

Before play started on the first morning in Durban, Alex Hales was presented with his England cap by Michael Atherton — back in South Africa as a commentator, twenty years on from captaining his country’s first post-apartheid tour there. It had included his greatest triumph, when he defied Allan Donald and Shaun Pollock for almost eleven hours, finishing on 185* and securing a draw in a Test which had seemed lost. He was ably assisted by Jack Russell, who scored only 29* but survived for more than two sessions. Michael Jones remembers one of the great match-saving innings that dates back to December 4, 1995.

A fan who has only known cricket in the 21st century may take a cursory glance at Michael Atherton‘s career statistics and dismiss them out of hand — an opening batsman with an average of under 40? While it is true that, among specialist batsmen with 100 or more Tests, Atherton’s 37.69 is the second lowest average (ahead of Carl Hooper’s 36.46), to denigrate his record on the grounds of a single statistic is to display a glaring ignorance of the vastly different era in which he played.

To illustrate the contrast between the task facing an opening batsman today and that of his counterpart two decades ago, let us first consider the best fast bowlers currently operating. Only Dale Steyn is unquestionably an all-time great; the recently retired Mitchell Johnson was devastating for two series against England and South Africa in 2013-14, but failed to approach the same level of performance for much of the rest of his career. Others such as James Anderson, Stuart Broad, Mitchell Starc and Morne Morkel fall short of the tag of ‘great’.

Now examine the state of fast bowling in the 1990s. Three pairs of greats carried their respective countries’ attacks throughout the decade: Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh, Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, Allan Donald and Shaun Pollock, with Glenn McGrath operating as a great backed up by a ‘not quite great’ in Jason Gillespie.

At the start of the decade Malcolm Marshall, Imran Khan and Richard Hadlee were still active, although all had retired before it was halfway through. Hardly surprising, then, that the decade was not a good one in which to be an opening batsman; only four players opened in 50 or more Tests during the period, and of those, Mark Taylor and Gary Kirsten both had averages similar to Atherton’s. Michael Slater, with 44, had the highest average of the quartet. In contrast, twelve batsmen have opened in 50 or more Tests since 2000, with Matthew Hayden and Virender Sehwag averaging over 50 and Graeme Smith, Justin Langer, Herschelle Gibbs and Alastair Cook not far off it. It is difficult to dispute, then, that opening the batting in Tests has become significantly easier since the turn of the century.

It is one of the more curious of cricket statistics that, on the list of most dismissals of the same batsman by the same bowler in Tests, Atherton occupies three of the top four spots, with 19 dismissals by McGrath, and 17 each at the hands of Ambrose and Walsh (the top four is completed by the 18 times Alec Bedser accounted for Arthur Morris).

There is a number of reasons for this: first, opening batsmen face opening bowlers all the time, and so have more opportunities to be dismissed by them; middle- and lower-order batsmen face a wider variety of bowlers, sometimes coming in when the openers are still on, other times when the back-up seamers and spinners are operating. Secondly, during the 1990s England regularly played six-Test series at home (at a time when there was no obligation to host another touring team the same summer), and five away, against both Australia and West Indies, with the result that Atherton played against them significantly more often than other teams. Thirdly, he was the only opener who stayed in the team long enough to be dismissed that many times: once Graham Gooch had retired and Alec Stewart moved to the middle order to enable him to keep wicket, Atherton had an on-off partnership with Mark Butcher, but otherwise no regular opening partner until Marcus Trescothick appeared on the scene: in the course of the decade the likes of Mark Lathwell, John Crawley, Jason Gallian, Steve James and Darren Maddy were all tried, failed and were quickly dropped again. There were two pillars of constancy in an ever-changing team, and although their styles could hardly have been more contrasting, they were permanently bracketed together: for a generation of England fans, the names of Atherton and Stewart were as inseparable as fish and chips.

Background

In 1994, South Africa had made their first tour of England since their readmission to international cricket; their thumping victory at Lord’s was overshadowed by the ‘dirt in pocket’ affair, which led to calls for Atherton to resign as captain. He answered his critics with a fighting 99 in a draw at Headingley.

At The Oval, Kepler Wessels made what turned out to be the decisive mistake in instructing Fanie de Villiers to bowl a bouncer to Devon Malcolm. De Villiers did as his captain requested, Malcolm was hit on the helmet and responded by destroying the visitors with second innings figures of 9 for 57; England cantered home by 8 wickets, with Atherton leading the charge, to level the series at 1-1.

Little more than a year later, England paid a return visit — the first time they had played in South Africa since the scheduled 1968-69 tour had been cancelled over the Basil D’Oliveira affair.

Both teams had undergone some changes in the intervening period: the Oval Test had been Kepler Wessels’ last, with the captaincy passing to Hansie Cronje; Peter Kirsten had also come to the end of his career, allowing his half-brother Gary and Andrew Hudson to secure the opening spots which they had previously had to compete with him for.

Among the visitors, Joey Benjamin had not been picked again despite his useful figures of 4 for 42 on debut, and Phil DeFreitas had been dropped after the first match of England’s series against West Indies the previous summer; Dominic Cork’s spectacular entry to Test cricket, with figures of 7 for 43 on debut followed by a hat trick two matches later, ensured that DeFreitas’ Test career was over. Peter Martin, who had also made his debut in the West Indies series, completed the seam attack for the South Africa tour. Jack Russell was preferred to Steve Rhodes as ’keeper, although the debate continued as to whether England should pick four bowlers and a specialist ’keeper, or five and give Stewart the gloves.

The friction in the England camp started before they even arrived in the country: Ray Illingworth still held the position of ‘supremo’ — coach, manager and chairman of selectors rolled into one — and it was hardly a secret that he and Atherton failed to see eye to eye. Their differences had been set aside for as long as the team celebrated a drawn series against West Indies, but soon came to the fore again: at the selection meeting, Atherton had wanted the last two batting places in the squad to go to Nick Knight and Nasser Hussain; Illingworth preferred Mark Ramprakash and John Crawley, and got his way, claiming he would “back his judgement of players against anyone’s”.

Anyone who felt inclined to lay a wager on their own judgement against Illingworth’s would have won fairly easily: Ramprakash scored 13 in three innings in the series, giving him a lower average than that of Angus Fraser, while Crawley only played one match and did not bat.

Relations between the manager and the players were not helped by Illingworth banning the squad members from writing newspaper columns during the tour, while seeing nothing wrong with writing for the Sun himself — nor by what he wrote in them, starting with a headline which, in a piece of rank hypocrisy coming from Illingworth, called Atherton “stubborn, inflexible and narrow-minded”.

Illingworth was not a man known for his ability to get the best out of each player by treating them as individuals: he believed that his approach should work for everyone, and any player who failed to fit in was labelled as ‘awkward’. He tried to persuade Malcolm to change his action — a ludicrous decision given that his existing one had been enough to annihilate the same opposition in their previous encounter — and the public fall-out between them became the talking point of the tour.

On a side note, Malcolm got on rather better with a guest who visited the touring team during a warm-up match in Soweto: Nelson Mandela’s helicopter landed on the outfield and he was introduced to the players — although, being a cricket fan, he knew who most of them were anyway. When he reached Malcolm, Mandela greeted him with the words “I know you. You are the destroyer.” The South Africans’ nemesis replied with a smile “I know you too, Mr President.”

Just as, a few years earlier, David Gower and Ian Botham had infuriated their captain Gooch with their relaxed attitude to training, Malcolm’s similar attitude put him on the wrong side of Illingworth.

When rested for one of the practice matches, he failed to turn up to the ground; Atherton, while clearly unimpressed with the bowler’s indiscipline, felt that a quiet reprimand was sufficient to express his dissatisfaction, but Illingworth and the bowling coach Peter Lever decided to air the matter to the press. Ensuring that Malcolm would not have a chance to defend himself by talking to reporters gathered by the hotel pool in his absence, they laid into him, Lever informing them that “He has just one asset — pace. That apart, he is a nonentity in cricketing terms.”

Illingworth later tried to deny that the word ‘nonentity’ had been used, but several of the journalists present had had their tape recorders running, which proved otherwise. While the reporters were gleeful at the plentiful supply of material to fill their column inches, Malcolm felt humiliated, the rest of the team and most of the fans were baffled as to why Illingworth had thought it necessary to air their grievances in public — and the South African camp were probably delighted that the England management were shooting themselves in the foot by demoralising their most potent strike bowler. The ill-feeling between Illingworth and Malcolm was to rumble on throughout the tour.

The first Test of the series, which was also the first to be played at Centurion Park, turned into a damp squib. The home team started well, with Stewart, Ramprakash and Thorpe all falling cheaply — the last of them a maiden Test wicket for the debutant Shaun Pollock — but Atherton and Graeme Hick added 142, and although Atherton was out for 78 shortly before the close, Hick carried on to 141 the next day, Jack Russell made an unbeaten 50 and England reached 381 for 9 shortly before tea.

At that point a thunderstorm intervened, and the rain continued on and off for the next three days, never relenting long enough to allow play to resume. England could perhaps claim to have had slightly the better of the five sessions of play which were possible, but it was hardly a decisive advantage. Most of the discontent in the South African camp was directed at Brett Schultz, for claiming he was fit to play then pulling up injured in his first over — although he carried on long enough to claim Stewart’s wicket — and at Craig Smith, the physiotherapist, for passing him fit.

One statistical curiosity to arise from the match was that Dave Richardson became the first wicketkeeper to reach the milestone of 100 Test dismissals without a single stumping among them — South Africa’s all-pace attack had never given him a chance — although the introduction of Paul Adams to the team enabled him to break his duck towards the end of his career.

The match

The teams moved on to Johannesburg, with neither having had a chance to claim dominance in the series. England decided a spinner was surplus to requirements at the Wanderers, so after not being picked for Durban, Malcolm was brought in to replace Richard Illingworth, becoming the first black player to represent England in a Test in South Africa. That was England’s only change from the XI who played in the first Test; the home team made two, with Schultz not risked again and Craig Matthews also left out, replaced by Clive Eksteen and Meyrick Pringle.

Atherton chose to put South Africa in and initially saw his decision vindicated when Cork dismissed Hudson for a duck. After that, though, Kirsten settled in, adding 71 with Cronje for the second wicket and 137 with Cullinan for the third. The four seamers had been so ineffective for most of the day that England were forced to resort to Hick’s gentle off-spin to dislodge Cullinan.

Cork removed Jonty Rhodes cheaply, and Malcolm finally clicked when he took the second new ball, finally having Kirsten caught behind for 110 — his maiden Test century — then adding Richardson for a duck. Brian McMillan made 35 and when he was trapped in front by Cork, stumps were drawn for the day with the home team 278 for 7. Pollock’s 33 ensured that they extended the total to 332 the next day — coincidentally, exactly the same total they had made in the first innings at The Oval. Cork finished with five wickets, Malcolm four, with Russell claiming six catches.

England’s reply started badly when Atherton chose the wrong ball from Donald to leave; it swung in and took out his off-stump. Ramprakash scratched around for almost an hour, managing a solitary scoring shot before Donald put him out of his misery by flattening his off stump.

Stewart and Thorpe guided the visitors to 109 for 2, but once Eksteen had Thorpe caught at short leg the innings declined to 200 all out, with only a fifty from Smith standing between South Africa and an even bigger lead; the innings ended when he pushed one back and McMillan dived to take the return catch. As it was the home team went in again 132 ahead, with stumps called for the second day after 5 had been added for no loss.

Malcolm had Kirsten caught behind early on the third morning, and when Hudson followed the same way to Fraser the home team were 29 for 2. If England thought they were clawing their way back into the match, Cronje and Cullinan quickly shut them back out of it. Cullinan eventually fell to a cross-batted swipe off Cork which presented such a dolly to Gough at mid-on that the batsman had started to walk off before the ball came down; the same bowler tempted Cronje, on 45, to poke at one outside off stump, giving Russell his ninth catch of the match — one short of the Test record, set by Bob Taylor against India in the Golden Jubilee Test of 1980.

The fifth wicket pair added 99 before Rhodes, on 57, edged Fraser; there was no slip in place, forcing Russell to dive full length and hold it inches off the ground in front of where first slip would have been — equalling Taylor’s record in a fashion which demonstrated that he deserved to be bracketed in the same class as ’keeper.

McMillan and Richardson put on a further 52 and although the latter fell shortly before the close, South Africa were 296 for 6 with 7.3 overs remaining in the day — when they chose to come off for bad light. Already 428 ahead, the decision seemed inexplicable, and given that McMillan had just hooked Malcolm for six, four, six off consecutive deliveries, he did not appear to be having too many problems seeing the ball.

Having already piled up enough runs to ensure that defeat was out of the question, the only thing which remained to be seen the next morning was when Cronje would decide to declare. Three of the last four wickets fell early — including Eksteen edging Cork behind, presenting Russell with a more straightforward chance and the opportunity to claim a new world record.

At 314 for 9, McMillan had a century in his sights, but only Donald remaining to help him get there; he slowed down as he closed in on the milestone, but Cronje seemed content to let him get there, and called the batsmen in as soon as the all-rounder brought up three-figures. The 50 runs added in the morning session only served to put an already unattainable target even further beyond reach, but the 92 minutes taken reduced the time England had to bat out to five sessions and four overs. Atherton got off the mark by cover driving Pringle for four, and he and Stewart reached lunch with no alarms.

Like any international player, Atherton had done his homework on the bowlers he was to face: he noted that Pollock’s bouncers were generally directed at the body, and were best either defended or left alone; Donald’s tended to be wider, allowing the batsman the chance to attack them with less risk. In the afternoon he started to take Donald on, pulling or cutting anything short; the opening partnership had reached 75 when Stewart was bowled by McMillan.

Ramprakash seemed unable to find a happy medium between attack and defence: after making a 35-ball 4 in the first innings, he came out swinging in the second, missed and had his stumps rearranged for a second-ball duck.

Atherton and Thorpe took England to tea with no further loss, but halfway through the evening session Pringle swung one back in to trap Thorpe in front. Hick managed one boundary before being caught behind off Donald; Smith joined Atherton, and they saw the side through to stumps at 167 for 4 — Atherton unbeaten on 82, Smith on 11. With the last pair of specialist batsmen at the crease, only Russell and the tail to come, South Africa were well on their way to victory.

That night

Atherton was usually uneasy when not out overnight: with the adrenalin flowing, he found it difficult to sleep. This time a quiet evening at the hotel helped him relax and forget about the match for a few hours, and he slept well. The next morning he focused once again on the task in hand.

Like many cricketers, he was superstitious, insisting that the exact conditions of his previous success had to be replicated in order for the success to be repeated, and he wore the same clothes as the previous day; he later commented “superstition was stronger than the smell or the discomfort”.

Another page in history

He continued to accumulate runs, but grew nervous as he neared his century, conscious that he had been dismissed for 99 in Tests twice already. One run away from the milestone, Atherton tried to turn a ball from Donald into the leg side; Kirsten at short leg misjudged the chance, it bounced off his chest and he failed in an attempt to grab the rebound. Atherton guessed that Donald would follow that with another short ball, was ready and smashed it through square-leg to reach his first Test hundred against South Africa. He hugged Smith, who, Atherton remembered, “recoiled, no doubt at the smell”. Soon afterwards, Smith tried to cut a short ball from Donald, and was caught by Pollock at third man for 44: 232 for 5.

That brought Russell to the crease — by no means the best batsman in the world, but certainly one of the most infuriating to bowl at. After his retirement from playing, he would go on to make a successful second career as a painter, but there was certainly nothing artistic about his batting. His most common ‘shot’, if it could be called that, was the leave: he would stand with his bat hovering near the line of the ball in case he would be required to play it, but once he was sure it was going to miss the stumps, pull the bat inside the line. He survived an early scare against the second new ball when Pringle missed a return catch, but with five wickets to take in the last two sessions, South Africa could still fancy their chances.

‘The zone’ is a concept often referred to in sport: a state of total concentration, where the player is certain nothing can go wrong. Atherton commented later that the Johannesburg innings was the only time during his career that he felt he was in it: he knew the bowlers were not going to get him out.

As afternoon progressed, he continued to accumulate runs, while Russell blocked anything he had to and left anything he didn’t, scoring just eight runs in the session. The change in attitude among the bowlers and fielders was noticeable: shoulders started to slump as they saw the victory, which had seemed certain at the start of the day’s play, begin to slip away from them. The Wanderers crowd, usually one of the most hostile in the world towards visiting players, fell quiet.

In the final session the scales had tipped from a certain defeat towards a probable draw, but Russell in particular was taking nothing for granted. Between overs he constantly jabbered “Remember Barbados” — a reference to the match there five years earlier when Russell’s own five-hour 55 had seemed set to save the match, but once he was dismissed in the last hour of play, Curtly Ambrose had ripped apart the tail and West Indies had won with a few overs to spare; Atherton had to point out that he couldn’t remember the match because he hadn’t played in it.

The bowlers sat nervously on the pavilion balcony: from assuming that their contributions would be irrelevant because the team was certain to lose anyway, they were now in the position that, if they were required to bat at all, their survival would be crucial. Cork and Fraser remained in the same positions on the balcony for the whole of the last two sessions, convinced that to move would trigger the fall of a wicket.

Atherton’s concentration was only broken when Cronje walked up to offer his handshake, conceding the draw. Atherton shook the hand, then he and Russell grabbed souvenir stumps and raced off with their arms around each other, hotly pursued by a fan waving a Union Jack, whom they managed to evade to reach the safety of the pavilion.

Back in the dressing-room, he could reflect on what he had achieved: his 643 minutes was a full two hours more than anyone else had — or has — batted in the fourth innings of a Test (Dilip Vengsarkar’s 522-minute 146* against Pakistan in 1979 remains the next longest). He and Russell, with a 277-minute 29* to add to his earlier wicketkeeping record, were adjudged joint Men of the Match; under the circumstances, the draw felt like a win. Even Illingworth, whom Atherton once described as “about as likely to give undue praise as the Pope was to condone abortion”, called it “one of the great innings of all time”. Cronje displayed a mastery of understatement in labelling it “a good knock”, which Wisden Cricket Monthly commented “was like saying that Mozart knocked up the occasional catchy tune”.

What followed?

The third Test at Durban was another rain-affected draw. South Africa’s innings consisted of three useful partnerships separated by two collapses: Hudson and Kirsten added 54 for the first wicket (although Kirsten’s contribution was only 8), then they lost 5 wickets for 34; Rhodes and McMillan put together 52 for the sixth, before another four fell for 14; and finally, from 153 for 9, Pollock and Donald put on 72 for the last wicket. Gough was injured, Fraser and Malcolm dropped, and Cork went wicketless; Mark Ilott, Peter Martin and Richard Illingworth shared the wickets.

Donald claimed Atherton and Thorpe early on, but Stewart and Smith held the innings together, and England had reached 152 for 5 when the rain which had already interrupted the first two days’ play returned to wipe out most of the third, and all of the fourth and fifth. The match was notable as the Test debut of Jacques Kallis, although he gave little indication of what was to come: he was caught behind off Martin for 1, and did not bowl.

Port Elizabeth remained dry long enough for a full match; the home team chose to bat and made 428, with Cullinan (91), Richardson (84), Kirsten (51), Rhodes and McMillan (49 each) all contributing.

Atherton scored 72 and Hick 62 in England’s reply, but the rest of the top order failed and from 200 for 7 it required a partnership of 58 between Russell and Illingworth to avoid the follow-on. They struck back in the second innings, with Cork and Martin reducing the hosts to 69 for 6, only a partial recovery instigated by Kirsten and Pollock enabling them to declare at 162 for 9.

England needed 328 to win in just over a day, but as Donald later put it “There was no pace or zip to the pitch… Hansie Cronje set defensive fields and they didn’t seem interested in the chase, so they ended up 189 for 3 and everybody was bored.” The only thing to liven up proceedings was the introduction into the Test team, following some success against England in the warm-up matches, of the 18-year-old left-arm spinner Paul Adams, whose action — involving arms, legs and head pointing in seemingly random directions before the ball was projected from a completely unexpected angle — led to him being labelled the “frog-in-a-blender”.

Thus the series still stood at 0-0 when the teams reached Cape Town for the final Test — where, for once, both pitch and weather suggested that a result was likely. Donald routed England with 5 for 46 on the first day, including Atherton for a duck, and it was only thanks to a four-hour 66 from Smith that they reached an eventual 153.

They hit back, with Cork, Martin and Mike Watkinson sharing the wickets, and with South Africa 171 for 9 they looked to be heading for something close to parity on first innings. Instead overthrows turned Adams’ first scoring shot in Test cricket into a five, and a few wayward overs later he and Richardson had added 73 for the last wicket.

England trailed by 91, and although Thorpe (59) and Hick (36) ensured that they only lost 4 wickets in wiping off the deficit, the last 6 went down for 19, with Pollock claiming his first five-wicket haul in Tests. The hosts needed only 67 to win, strolled home by ten wickets — and the visitors started looking for someone to blame for the series defeat.

Illingworth, predictably, picked Malcolm as his scapegoat; while it was true that he had failed to break the last-wicket partnership, so had all the other bowlers until the match had swung decisively, and Malcolm had more excuse than most for being out of sorts, since thanks to poor management he hadn’t played for a month before being picked for Cape Town. Illingworth might have done better to reflect on the fact that of the 22 innings played by England batsmen in the match, only three produced more than 20 runs.

England contrived to lose the first ODI of the series by 6 runs despite having only needed 57 to win with 7 wickets in hand, won the second — in which Atherton was Man of the Match for his 85 — then got steadily worse for the rest of the series and eventually lost it 6-1, despite Cork setting a record for most consecutive dismissals of the same batsman, accounting for Kirsten five matches in succession.

South Africa progressed to the World Cup with their form and confidence sky-high, England at rock bottom, and both sustained the pattern during the group stage — the former winning every match, the latter scraping through to the quarter-finals with victories over Netherlands and UAE, losing to all the other Test teams in the group.

Both, though, made their exits at the same stage: England were hammered by the eventual champions Sri Lanka, while Brian Lara’s century was followed by something as rare in the modern era as a penguin in Karachi — a match-winning performance by a pair of West Indian spinners. Jimmy Adams and Roger Harper were no Ramadhin and Valentine, but they took seven wickets between them — Ambrose and Walsh only managed one each — to send South Africa crashing out, and make an early contribution towards their label of ‘chokers’.

The two sides resumed battle in England in 1998, when Atherton and Donald faced off at Trent Bridge in what both protagonists described as the most intense passage of play in their careers. Once again Atherton came out on top, although he required a helping hand from the umpire who failed to detect the impact of ball on glove in answering a caught behind appeal from Donald; he finished on 98*, England won by 8 wickets and ultimately snatched a 2-1 victory despite being outplayed for much of the series.

After the 185*, Atherton played two further international matches at Johannesburg — an ODI on the same tour and a Test four years later — faced 4 balls, and made 3 ducks. In 1999 Donald and Pollock reduced England to 2 for 4 on the first morning of the match, and finished with 11 and 8 wickets respectively; South Africa won by an innings. His ground record score was broken by Greg Blewett’s 214 in 1997, and has been beaten three more times since; it remains the best by an England batsman in South Africa post-readmission.

Russell’s record of 11 catches in a Test was equalled by AB de Villiers against Pakistan on the same ground in 2013, but has yet to be surpassed. His 277-minute 29* also retains its place in the list of the slowest innings: no-one has batted longer than that for so few runs.

Brief scores:

South Africa 332 (Gary Kirsten 110, Daryll Cullinan 69; Dominic Cork 5 for 84, Devon Malcolm 4 for 62, Jack Russell 6 catches) and 346 for 9 decl. (Daryll Cullinan 61, Jonty Rhodes 57, Brian McMillan 100*; Dominic Cork 4 for 78, Jack Russell 5 catches) drew with England 200 (Robin Smith 52) and 351 for 5 (Michael Atherton 185*).

Man of the Match: Michael Atherton and Jack Russell.

(Michael Jones’ writing focuses on cricket history and statistics, with occasional forays into the contemporary game)

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.