The Gilbert Jessop Mystery is a tale of detection etched on a vast canvas. A cricket historian plays the role of an expert hired to solve an intriguing problem involving old scoring sheets, fast hundreds, modern-art masterpieces, antique wagon wheels and old Victorian letters.

As he puts together pieces of the puzzle, he gets entangled in a bizarre mystery which spans across a century in time encompassing subjects as varied as Victorian England, the last days of British Raj, Scientific influence on Art and the Internet.

This novella is available in the volume Bowled Over – Stories Between the Covers by Arunabha Sengupta.

—

“You were locked in that place?” I gasped in disbelief.

Sareen was still smiling, but underneath the distant nightmare rippled across his features.

“Yes. After being shot in the right elbow, I was dragged to the hiding place and pushed into it. I think I was left to die slowly. I had no idea where I was. It was in the dead of night that I was rescued. And even then I had no idea where I was. It was only when I saw the email about the location of the hiding place that I became sure that it was one and the same.”

I looked at his missing arm and a sense of horror washed over me, but when I spoke bitterness took the upper hand.

“Surely, it must have added greatly to the general appeal of revenge, to have Mangalsingh shot and left to die in the same place?”

Sareen looked at me with calm, expressionless eyes. “Yes, I guess there was some added appeal.”

“Glad that we agree,” I retorted, but could not help following it up with – “And who was it that saved you?”

“Surely, you must have deduced it by now, Professor. It was our old friend, Paul Hackensmith.”

For a moment I stood there completely speechless. The whole story seemed too incredible. To me, Paul Hackensmith had retreated back into the leather-bound book of letters once he had delivered the painting to Ajaysingh. That he could play a part in the amazing chain of events just did not seem feasible.

“Why … why was there no mention of this rescue in any of the letters?” I found my tongue at last. “I’d have thought it was an event worth mentioning.”

Sareen shrugged.

“You see, professor, Paul was a traditional Victorian gentleman with very liberal ideas on art, but very conservative ones when it came to deciding what was fit for the eyes and ears of a lady. He seldom wrote to Liz about the gruesome war which happened to be the subject of some of his paintings and poetry. The shooting of a native Indian and his being dragged to a dungeon and being left to die was not his idea of a story fit for his Liz. Elephants, Maharajahs, cricket matches … Kipling’s Gunga Din perhaps. That’s all about India that Paul would share with her. ”

There was still something that still did not make sense.

“Hey, but wait. How is it possible? The combination that worked was 6996. The well-known tally of Bradman’s Test runs. Hackensmith was in Jaipur in 1946. Bradman still had two seasons to play.”

Sareen nodded.

“You think that vain old fool, Ajaysingh, would set the combination to 6996? No, professor. It was 1124. The total number of runs had had made off the dollies bowled to him in first-class cricket.”

“What about…?”

“Cricket often creates curious puddles of idiosyncrasies in the life of the adherent. Professor, I don’t think anyone could agree to that more than you. Jay is such a fanatic. Even while walking out after committing the only murder he ever would, he could not bear to let the combination to a treasure trove of cricketing curiosities stay as it was. He changed it to 6996.”

This eulogy of Jay Sareen was getting on my nerves. I looked Sareen in the eye.

“A proud father, aren’t you? Gushing about a son who kills an old man – revenge for a crime his father had committed.”

Sareen kept smiling as he walked forward and placed his solitary hand on my shoulder.

“There, professor, I told you that some of the mistakes in your theory can’t be helped. However, I can still help you out of this misconception.”

He put his left hand in the pocket of his coat and brought out an envelope. It was a very old one, yellow and brittle with age. It was addressed to Charles Mead, Esq., Cromwell, Nottinghamshire, England.

I opened it with unsteady hands. Premonition perhaps, but I seemed to know what it contained.

The first thing that struck me about the letter was the exquisite handwriting, calligraphy of the finest order. The second striking factor was the age. And finally it was the content that held me transfixed.

Calcutta,

27th January, 1946.

Dear Charlie,

I hope you are well.

I have a rather strange request of you, and knowing you to be the kind of person you are, I have no misgivings about the trust that I am about to place in you.

The Indian youth who has brought you this letter has had an arm amputated. It is to his severest misfortune, even more than ordinary, because this young man was shaping into one of the finest Indian medium pace bowlers of his generation, if not into a name to be reckoned with in the whole world.

Please see to it that he obtains some decent mean to earn his livelihood. He has had to undergo a lot of suffering in recent times. You would oblige me greatly if you arrange for his well being.

The story that I am about to relate is strange. In these days of modern thought, when the good old feudal spirit has already bid a not too graceful farewell, it is amazing what atrocities still exist in some parts of the world where remnants of such ritual still hang on to the edge of time. That too in the wake of the Second Great War, which has shown human beings the true consequences of hating each other.

I had returned late at night, having been busy attending a party thrown by our host, Kumar Ajaysingh. The moon was out in its full bloom. Advanced years make sleep a faithless companion and so, to keep myself occupied, I was reflecting on my current dream of capturing Mathematical thought from Fermat to Liebnitz in a single painting of curves. Thinking it would stimulate my thoughts, I decided to take a walk on the terrace.

The strong, silvery moonlight enabled me to save the life of this young man. From the terrace, I noticed a group of men dragging him into a clearing behind the palace. I recognised the lad because I had seen him bowl with great skill in the afternoon for the home team against visiting servicemen. He had also tossed up some friendly deliveries at Ajaysingh just before the banquet. I had no idea what the hoodlums wanted from him and was about to arouse the household when I saw the Kumar himself walking into the clearing with his seventeen year old son.

Ajaysingh carried a whip and he wielded it with a certain amount of relish I would not have believed possible from the gracious host who had entertained us so lavishly for the past few days. Kumar Mangalsingh, his seventeen year old son, was not far behind. He wielded a small stick, which, judging by the reaction of the captive, seemed to end in a sharp edge.

The surrounding goons contributed their share with the occasional kick and punch.

Just when I felt that the worst was over, my gracious host did something I was not at all prepared for even after all this. Taking out his favourite Smith and Wesson from his holster, he handed it with a show of magnanimity to his son. Almost ecstatic with joy on receipt of this new plaything, the seventeen year old Mangalsingh shot at the cowering captive. The bullet seemed intentionally aimed at the elbow of the youth. As he writhed about in agony, the young prince turned respectfully towards his father and returned the weapon of destruction. Then he walked off, presumably to finish a game of chess or some other diversion that had been interrupted for this noble purpose.

Ajaysingh and his henchmen, meanwhile, dragged the poor boy away from the house. In spite of my seventy five years, I could not help but follow them at a distance in the faint hope of being able to do something for the boy. And indeed, opportunity did knock on my door.

They took the lad to the RRCC ground and then into the clubhouse. By then I was sure where they were heading. I hid myself behind a tree and waited for them to come out. They did so in a quarter of an hour. Circumspect, I entered the clubhouse. Our host had shown us the hiding place that evening. He had also been gracious enough to demonstrate how to open and close the trapdoor that led to the secret chamber. There was a numeric combination to be used to open the door, which the vain ruler had set as 1124, his collection of runs in first class cricket.

I used the combination to open the trapdoor and went in. Using my matches for light, I reached the room where all sorts of cricketing treasures were kept. I had been right in deducing that the boy was there. He was alive, bleeding profusely and in excruciating pain.

I hastened to free him of the rope that bound him and helped him up the stairs. And then, making our way to the stables, we borrowed a horse and rode to a nearby house of a physician I knew. I kept him there for the night and returned to the palace. The next day, after bidding a hasty farewell to our host, I left town, collecting the injured youth on the way.

I got him admitted in one of the best hospitals and there he had to be operated on. His right arm, his bowling arm, had to be amputated. Added to this misfortune, was his constant trepidation. He believed Ajaysingh would hunt him down and kill him. The reason for the rage of this prince seemed to be his refusal to bowl long hops while he was having a hit in the nets that fateful day.

I am sending him across on the next boat. I spoke to Wavell about the atrocity of Ajaysingh, but he thinks it would be a waste of time to get involved. As he put it in his impeccable way,

“But, Sir, there are nearly six hundred Maharajas in this nation. It would take another World War to stop all such incidents.”

One of his aides added. “And then, Sir, it is to our benefit. Better their blood than ours.”

War as a means of stopping violence. Bloodshed that is beneficial. Well, these eternal paradoxes make up civilization.

My only regret is that the painting which had been the passion of several years of my life now remains in the treasury of a tyrant. But it is a small enough price to pay for a young life.

-Sincerely,

Uncle Paul.

I was so riveted by the letter that Sareen had to clear his throat to indicate that he was still there.

Kumar Mangalsingh! That same Mangalsingh I had respected so much, the sober, suave, intelligent and philanthropic Kumar. He had beaten up and shot an innocent, helpless young man whose only fault had been to bowl too well?

“How do you feel now, professor?”

I shook my head.

“I don’t really know, Mr. Sareen. It’ll surely take time to sink in.”

I handed the letter back to him. He took it with his left hand. Then, with an elaborate movement, he picked up the package he had brought with him.

“I’ll leave you with your thoughts, professor. But before that there is one more thing. This present comes from my daughter-in-law, with her best regards. Both she and my son feel that you are the only one worthy of possessing this. I took the opportunity of your being in Englandto get in touch with you and hand this over.”

He handed me the package.

I tore it open with hands that no longer had any feeling in them and stole a glance at the contents. Then I looked at Sareen. He was walking out of the room, waving at me with his solitary hand and smiling. I could only nod in answer as he disappeared from sight in the same unreal way as he had appeared.

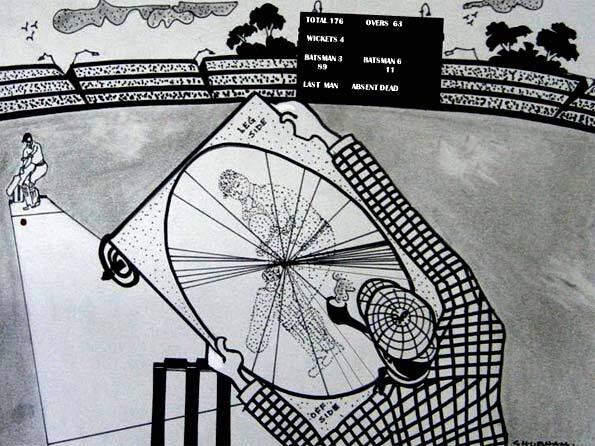

In my hand was an amazing amalgam of colour. It was the depiction of an oval with arcs and curves denoted in spectacular, separate colourful three-dimensional brush strokes, each ending with a digit at the end. The title – Jessop’s Jubilee – Illumination Thirty Seven Days Later was clearly inscribed in the same exquisite calligraphy as in the letter I had just read. The signature – Paul Hackensmith – was visible at a corner of the field. Directly above the signature, a swirling curve had crossed the edge of the oval and had ended in a single digit – 4. It was the famous cut over the slips off Milligan that had gone over the boundary, but because of the old rule for sixes, had been counted as four runs. Beyond the oval was a depiction of the crowd in a fuzzy form, maybe an experiment with the time component. The whole effect was that of a spectacular display of fireworks.

Each stroke was done in a separate colour, of slight, subtle but distinguishable variation of shade. The brushstrokes were of different boldness and made me wonder whether it was an attempt at portraying the force associated with the strokes and the velocity of the travelling balls. It would take some time to find out how the shades represented the sequence of deliveries and whether any other story was eloquently hidden behind the work, but now the painting would receive all my available time.

.1.4.143.613144411..44….44141.1.644146.44.64 OUT

This novella is available at John McKenzie Cricket Bookshop

(Arunabha Sengupta is trained from Indian Statistical Institute as a Statistician. He works as a Process Consultant, but cleanses the soul through writing and cricket, often mixing the two. His author site is at http://www.senantix.com and his cricket blogs at http:/senantixtwentytwoyards.blogspot.com)

Click here for the earlier parts